Those of you who read this blog regularly or follow me on Twitter will know that since October I have been harassing public authorities and Members of the Scottish Parliament in relation to the case of Cadder v HM Advocate and the resulting changes to the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995. In January, to mark the end of the first three months of the aforementioned changes I made requests to all eight Scottish Police forces in Scotland, and the British Transport Police as well as the Scottish Government in relation to this case. I am determined that the difficult questions will be asked and answered and those responsible for taking decisions are held to account. It is my view that the Scottish Government failed in relation to this case and that it could have been a lot more pro-active.

This blog post is simply to update everyone on exactly what has been happening and at what stage everything is at.

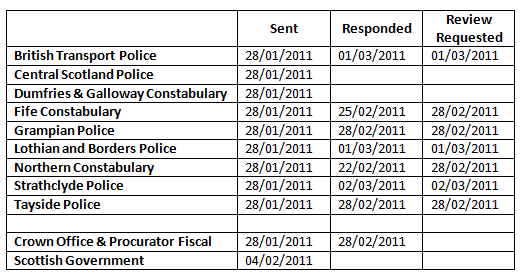

As you can see from the image above there are two Scottish Police forces and the Scottish Government left to respond to my request and all are overdue. Under the terms of the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 a Scottish public authority has 20 working days to respond to a request made.

The Scottish Government did send me an E-mail late on Friday evening advising that due to sickness my response would be delayed. Unfortunately not a lot can be done about the person dealing with my request being sick and so I am hopeful to hear back from them in the next few days.

Both police forces who have not yet responded have sent acknowledgments to my request and have not requested any clarification on matters (as when they do the FOI clock stops until such times as they have received from me to the clarification sought). As such I intend to contact the Forces initially by telephone to see what is holding the requests up and then may refer the matter to the Information Commissioner for Scotland as a failure to respond. Their responses are now more than one week overdue!

Each police force who has responded to date has found a reason not to release the information requested, largely it comes down to a matter of cost. In fact, in all cases cost is at least part of the reason as to why the information sought has not been provided. They have all argued that their systems do not allow for the search to be carried out anyway other than for a person to sit down and manually go through custody records. I’m not an expert on IT nor am I an expert on the systems they use, but I do find it quite hard to believe so have therefore requested a review to be carried out by each force. I have made many FOI requests before, but have never, until now, made a request for a review. The matter is far too important for a refusal at the first stage simply to be accepted.

The Crown Office responded in full at the first stage.

I have began collating what I have to date in terms of information and hope that by the middle of next month will be in a position to come to some conclusions and put any difficult questions that need to be answered to the appropriate people (quite how that will happen I am not all that sure, but I will find a way!) It would be great to be able to get these questions out there in advance of the Scottish Parliamentary elections on 5 May 2011 as the Government may well be different which will make accountability a bit harder.

——

Updates

Central Scotland Police are chasing the person responsible for providing the information and hope to respond in the next few days either with a response or with an update as to what is happening.

I was unable to speak to anyone at Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary by telephone (number listed for them directs to Grampian Police!) so have sent an E-mail to them seeking an update and advising them that the 20 working day period has now expired.

Central Scotland Police have again been in touch advising that the individual responsible for gathering the information is out of the office until tomorrow (09/03/2011) and will be in touch again soon with a further update.

Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary have responded to my request for an update stating that they “are currently looking at our system to establish what information can be retrieved” and that they will get back to me “as soon as possible.”

Now only the Scottish Government is to respond to the Freedom of Information request.

Last updated: 12/03/2011 at 18:08

As you can see from the image above there are two Scottish Police forces and the Scottish Government left to respond to my request and all are overdue. Under the terms of the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 a Scottish public authority has 20 working days to respond to a request made.

The Scottish Government did send me an E-mail late on Friday evening advising that due to sickness my response would be delayed. Unfortunately not a lot can be done about the person dealing with my request being sick and so I am hopeful to hear back from them in the next few days.

Both police forces who have not yet responded have sent acknowledgments to my request and have not requested any clarification on matters (as when they do the FOI clock stops until such times as they have received from me to the clarification sought). As such I intend to contact the Forces initially by telephone to see what is holding the requests up and then may refer the matter to the Information Commissioner for Scotland as a failure to respond. Their responses are now more than one week overdue!

Each police force who has responded to date has found a reason not to release the information requested, largely it comes down to a matter of cost. In fact, in all cases cost is at least part of the reason as to why the information sought has not been provided. They have all argued that their systems do not allow for the search to be carried out anyway other than for a person to sit down and manually go through custody records. I’m not an expert on IT nor am I an expert on the systems they use, but I do find it quite hard to believe so have therefore requested a review to be carried out by each force. I have made many FOI requests before, but have never, until now, made a request for a review. The matter is far too important for a refusal at the first stage simply to be accepted.

The Crown Office responded in full at the first stage.